Accurate temperature measurement inside a furnace is never just about pointing an instrument and taking a reading. In real operating environments, surfaces change, backgrounds vary and conditions are rarely ideal.

That is why correct setup and a clear understanding of infrared fundamentals matter so much when carrying out furnace imaging and tube temperature surveys.

During a recent technical session with customers, I walked through the practical realities of infrared measurement in furnaces, drawing on real examples from field experience. What consistently stands out is that reliable data does not come from shortcuts. It comes from understanding the physics behind the instrument.

The three fundamentals that underpin every measurement

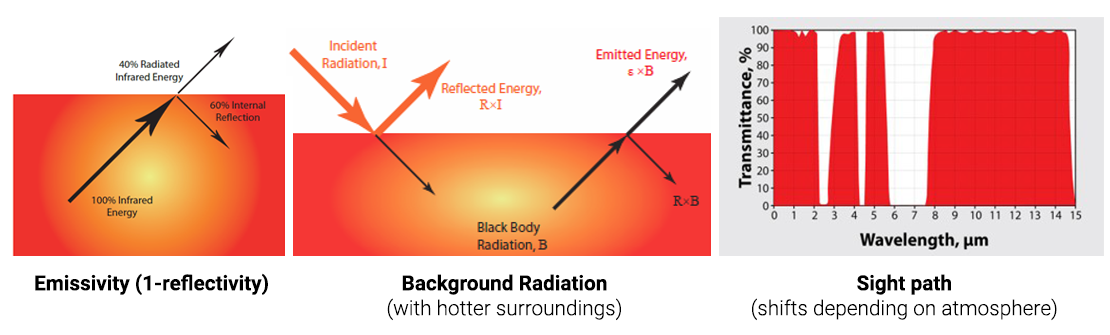

Infrared temperature measurement always comes back to three connected factors that need to be considered together: emissivity, background radiation and the sight path.

Emissivity describes how efficiently a surface emits energy compared to an ideal black body. A perfect emitter (emissivity 1.00) would re‑emit all the energy it receives. In practice, furnace tubes never behave that way as they are not perfect emitters. Over time, emissivity changes with temperature, surface condition, tube metallurgy and the effects of coking and material ageing. Assuming emissivity is fixed or uniform can quickly introduce error.

Background radiation is equally important. When emissivity is less than 1.00, part of the energy detected by an infrared instrument is coming from the background reflected off the tube rather than the tube itself. Hot refractory walls and furnace geometry both contribute reflected energy that can distort apparent tube temperature if it is not properly accounted for.

The sight path completes the picture. Infrared measurements rely on energy passing through the atmosphere between the target and the detector. Certain wavelengths are chosen because they transmit well through combustion gases, allowing measurements to be taken with minimal loss. Choosing the right wavelength is always a balance between sensitivity to background radiation and sensitivity to changes in emissivity.

Why wavelength choice is a balancing act

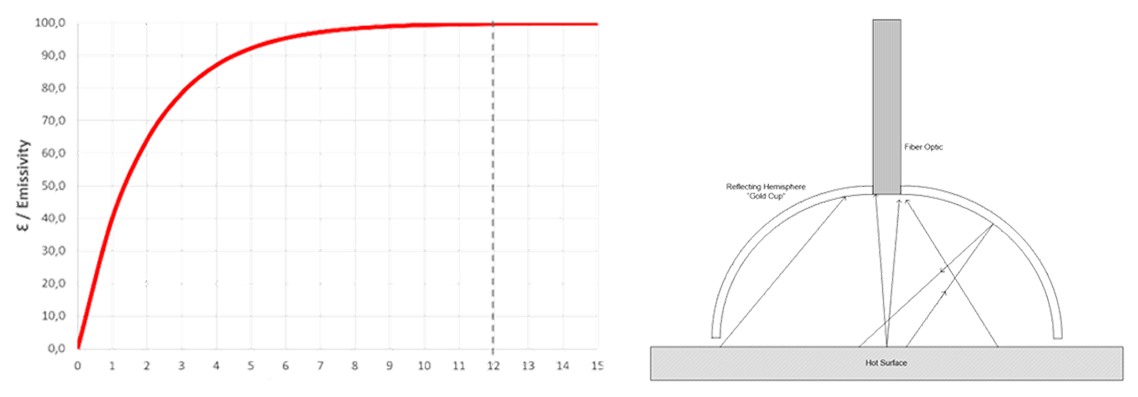

In furnace applications, the common wavelengths are 1μm and 3.9μm. Shorter and longer wavelengths each have advantages and limitations. Shorter wavelengths are less sensitive to changes in emissivity but more affected by reflected background energy. Longer wavelengths reduce the impact of background reflections but increase sensitivity to emissivity variation.

Neither option is universally right or wrong. The correct choice depends on the application, the measurement method and the practical constraints of the survey. Understanding these trade-offs is far more important than trying to identify a single “correct” wavelength.

Enhancing emissivity with the Gold Cup

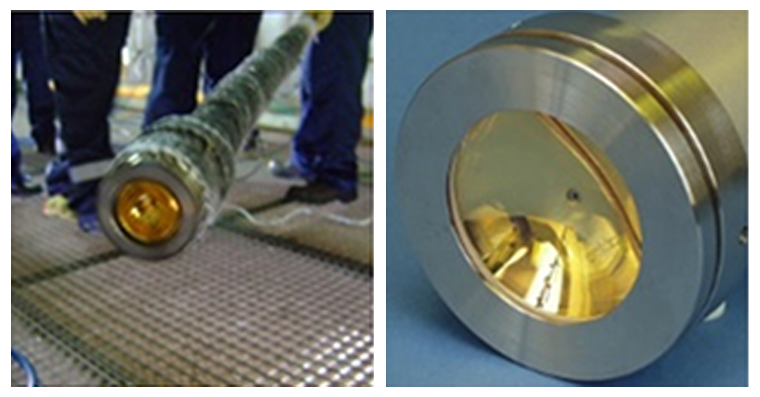

One of the most effective ways to reduce uncertainty in measurements is by using a reference to validate the infrared measurement. This is where the Gold Cup becomes particularly useful.

The Gold Cup works by reflecting radiation multiple times before it reaches the detector. Gold is an exceptionally good reflector and by using a conical reflective geometry, the system forces the radiation to undergo many reflections. After enough reflections, the measurement behaves as if it is coming from a near-perfect emitter.

In practical terms, this allows operators to assume an emissivity very close to 1.00 at the measurement point. Because the Gold Cup is in contact with the tube, the influence of background radiation is none. It does not remove uncertainty entirely, but it provides a reliable reference that can be used to calibrate and correct thermal imaging or pyrometer data periodically.

Why technique matters just as much as the instrument

How the Gold Cup is used is just as important as the instrument itself.

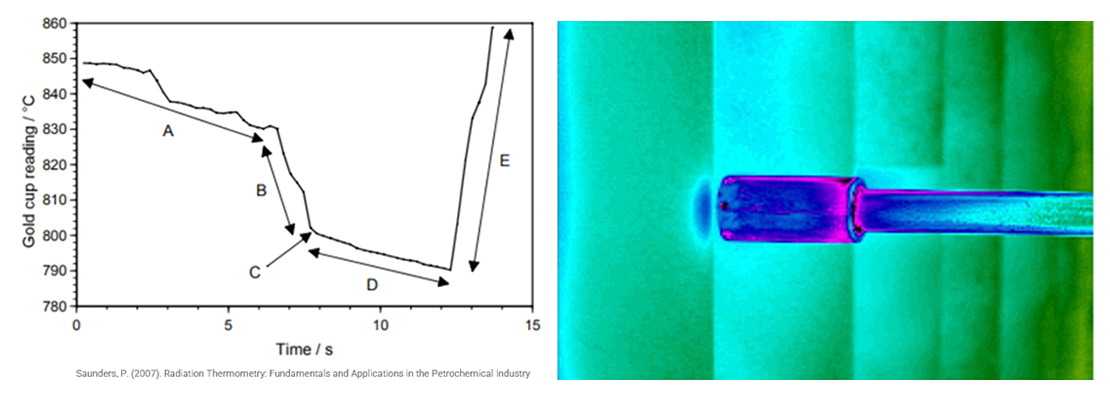

As the probe approaches a tube, the apparent temperature changes as the background influence reduces and then when very close, the reflected energy decreases as you get close to touching. The ideal measurement point is when the Gold Cup just makes contact with the tube. At this moment, background influence is zero and the probe hasn't started to cool the tube.

Leaving the Gold Cup in contact with the tube for too long can artificially cool the surface. This creates a local cold spot and reduces the measured temperature. Moving too slowly or pausing near the tube can also introduce variability as the measurement could be effected by the draft effect of having the peep door open.

Consistency in insertion technique, taking one tube at a time and allowing the furnace environment to stabilise between measurements all help improve repeatability and confidence in the results. We would also advise that a peep door cooling test is completed to understand the cooling effect of opening the peep door and to give an idea of uncertainty on the Gold Cup measurement.

The importance of clean optics and repeatability

Dust and contamination can have a significant effect on measurement accuracy. Even small amounts of dust on optical components or the fibre light guide can greatly reduce transmitted energy, leading to clear drops in measured temperature.

Rather than showing up as slow drift, this typically appears as a sudden and obvious change, which can be a useful diagnostic in itself. Keeping reflective surfaces clean and carrying out regular checks against a known reference furnace helps maintain confidence in the data.

Repeatability is equally important. Environmental conditions such as wind direction, open peep doors and operator activity all influence measurements. Simple sanity checks, such as monitoring temperature changes after opening a peep door, help Gold Cup users understand how much time they have to take reliable readings.

Turning reference points into usable insight

Gold Cup measurements are most valuable when they are used as a reference rather than viewed in isolation. Their strength lies in helping to calibrate emissivity and background correction within thermal images.

By anchoring image analysis to a trusted reference point, users can interpret temperature data with greater confidence across a wider area of the furnace. This makes it possible to understand temperature trends along tube lengths even where direct reference measurements are not practical at every location.

This approach also supports more conservative decision-making by selecting emissivity values that avoid overstating tube temperature.

Confidence comes from understanding, not assumptions

There is no single rule that applies to every furnace, every survey or every site. Infrared temperature measurement always involves assumptions. What matters is understanding those assumptions, recognising their limitations and applying them consistently.

The Gold Cup is not a silver bullet on its own. It is a practical tool that, when used correctly and combined with a solid understanding of infrared physics, helps reduce uncertainty and supports better-informed decisions whilst not interrupting operational conditions of customers assets.

Ultimately, correct setup is about more than equipment. It is about combining physics, experience and disciplined techniques to produce measurements that operators can trust.

To learn more about LAND’s temperature measurement solutions, click here.